For decades, growers have relied on conventional polyethylene (PE) plastic mulch for its many benefits as it helps control weeds, conserve soil moisture, warm the soil for earlier harvests, increase crop yield and quality. These advantages have made PE mulch a staple in the production of high-value crops like strawberries and vegetables. However, the convenience of PE mulch ends when the season is over. Removing PE mulch is labor-intensive and costly. Recycling is often not a viable option for used PE mulch because it can be heavily contaminated with soil and plant debris, up to 80% by weight (Dong et al., 2022). Even with careful removal, 5% to 10% of the plastic can be left in the field depending upon method of removal, soil types, and length of the time in the field, further breaking down into persistent micro and nanoparticles that pollute the soil for centuries (Ghimire et al., 2018a; Tiwari and Sistla, 2024). These end-of-life challenges have led to question the long-term sustainability of PE mulch, paving the way for alternatives like soil-biodegradable plastic mulch (BDM).

What is Biodegradable Plastic Mulch?

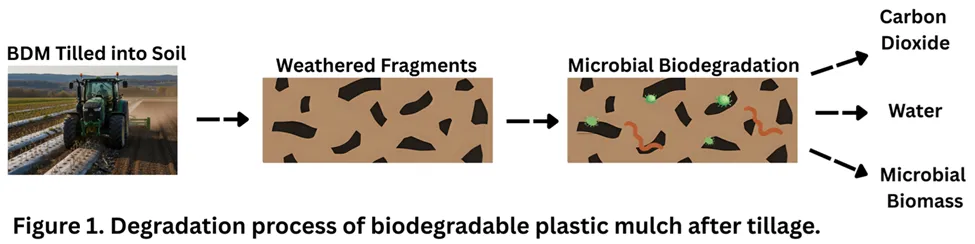

Soil-biodegradable plastic mulch is a film designed to be tilled in the soil at the end of growing season and broken-down by soil microorganisms into carbon dioxide (CO2), water, and microbial biomass (Miles et al., 2017).

What are BDMs made of? Commercially available BDMs are typically blends of biobased and fossil fuel-based polymers. Biobased feedstocks include starch often from corn, polylactic acid (PLA), and polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA). Fossil fuel-based but still biodegradable feedstocks include polymers like poly(butylene-adipate-co-terephthalate) (PBAT) and poly(butylene succinate) (PBS). In addition to these primary polymers, BDMs also contain various additives, including plasticizers, to improve their properties and performance (Ghimire et al., 2018a).

Beware of oxo-degradable products. It is important to understand that "biodegradable" is not the same as "degradable." Some products, often called "oxo-degradable" plastics, simply fragment into tiny plastic, do not fully break down and contribute to microplastic pollution (Miles, 2017).

The Degradation and Soil Health Question

The European Standard EN 17033 is a key benchmark, requiring that BDMs achieve at least 90% biodegradation in soil within two years under controlled laboratory conditions. In the field, degradation rates depend heavily on factors like film characteristics, soil temperature, moisture, and microbial activity. Under warmer climate such as Central Valley of CA biodegradation is expected to be relatively faster. Accurately estimating the in-field biodegradation of BDM mulches is challenging due to problems associated with recovering tiny (macro and nano) plastic fragments from the soil samples. A modeling approach estimated that it would take ~34 months in Watsonville, CA, to accumulate the thermal time needed for 90% biodegradation achieved in a standard two-year laboratory test (Griffin-LaHue et al., 2022). Using the same model, this process would take ~32 months in Fresno, CA. These findings show that mulch degrades more rapidly under the controlled conditions of a laboratory than in real-world field scenarios.

A primary concern for any grower is the long-term health of their soil. Conventional PE mulch is a source of microplastic pollution in agricultural soils. Fragments left after removal break down into smaller pieces that persist for hundreds of years, potentially altering soil structure, water movement, and microbial communities. BDMs also create microplastic fragments as they break down, but these fragments are temporary as they undergo biodegradation by soil microbes (Fig. 1). Short-term and medium-term studies (up to 4 years) have found that the use of BDMs have minimal impacts on soil properties including soil pH, water holding capacity, aggregate stability, microbial activity and organic matter when compared to PE mulch (DeVetter, 2025). However, the question of long-term repeated use of BDM on soil ecosystem requires further investigation.

Biodegradable Plastic Mulch Performance Compared to Conventional Polyethylene Mulch

Both PE mulch and BDMs are effective tools for weed control compared to bare ground cultivation, though effectiveness depends on the specific BDM product, crop, climate, and particular field challenges like weed type. Many studies have found that BDM performance in suppressing weeds is comparable to that of PE mulch given that BDM remains sufficiently intact throughout the critical period of weed control for a given crop (DeVetter et al., 2017; Ghimire et al., 2018b).

While pernicious weeds like yellow and purple nutsedge can penetrate both PE and plastic BDM films, paper mulch has been shown to effectively prevent nutsedge emergence (Moore and Wszelaki, 2019b).

Research across various specialty crops, including tomato, broccoli, pumpkin, pepper, strawberry, and melon, shows that yields are often equivalent between BDM and PE mulch treatments (Cowan et al., 2014; DeVetter et al., 2017; Moore and Wszelaki, 2019a; Shcherbatyuk et al., 2024). A meta-analysis concluded that despite potentially lower weed suppression, crop yields are not significantly different between BDMs and PE mulch (Tofanelli and Wortman, 2020).

Fruit quality is generally maintained and comparable between BDM and PE mulch. However, a potential drawback for crops with heavy fruit that rest on the mulch, such as pumpkin, is the adhesion of BDM fragments to the fruit surface, which can affect marketability (Ghimire et al., 2018b).

Economic Considerations

The economics of BDM involve a trade-off between higher upfront material costs and end-of-season savings. BDM rolls are more expensive than PE mulch rolls, two to three times the price. The primary economic advantage of BDM is the elimination of labor costs for removing the plastic and the subsequent disposal fees. BDM requires the additional labor of being tilled into the soil after drip tape removal. An interactive Mulch Calculator has been developed that allows you to input your specific costs for, materials, labor and disposal to compare the economics of PE and BDM for your operation (Chen et al., 2018).

Key Take Aways

- Soil-biodegradable plastic mulch designed to be tilled in the soil provides similar agronomic benefits as PE Mulch.

- Current research indicates that BDM impacts on soil health are minimal, but effect of long-term repeated requires further investigation.

- The decision to adopt BDM requires a careful calculation of whether the savings from eliminating PE removal and disposal can offset the higher initial product cost.

- No commercially available plastic BDM is currently approved for use in certified organic production in the U.S. because none meet the USDA National Organic Program's 100% biobased content requirement.

- If you are looking for an alternative to plastic mulch, testing BDM on a few beds could be a logical next step for your farm.

Have Questions

We've covered a range of aspects on biodegradable plastic mulch. If you're using, considering, or just curious about BDMs, please feel free to reach out with your specific questions to:

Manpreet Singh

Technology and Innovation for Small Farms Advisor

(559) 646-6535

References

Chen, K.-J., S. Galinato, S. Ghimire, S. MacDonald, T. Marsh, et al. 2018. Mulch Calculator. https://biodegradablemulch.tennessee.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/214/2020/12/Chen-Mulch-calculcator-introduction.pdf (accessed 25 September 2025).

Cowan, J.S., C.A. Miles, P.K. Andrews, and D.A. Inglis. 2014. Biodegradable mulch performed comparably to polyethylene in high tunnel tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) production. J Sci Food Agric 94(9): 1854–1864. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.6504.

DeVetter, L. 2025. Sustainable Mulch MANAGEMENT Plastic Mulches in Horticulture Production. 4(2). https://smallfruits.wsu.edu/documents/2025/05/sustainable-mulch-management-spring-2025.pdf/ (accessed 25 September 2025).

DeVetter, L.W., H. Zhang, S. Ghimire, S. Watkinson, and C.A. Miles. 2017. Plastic biodegradable mulches reduce weeds and promote crop growth in day-neutral strawberry in Western Washington. HortScience 52(12): 1700–1706. doi: 10.21273/HORTSCI12422-17.

Dong, H., G. Yang, Y. Zhang, Y. Yang, D. Wang, et al. 2022. Recycling, disposal, or biodegradable-alternative of polyethylene plastic film for agricultural mulching? A life cycle analysis of their environmental impacts. J Clean Prod 380. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.134950.

Ghimire, S., D. Hayes, J. Cowan, D. Inglis, L. DeVetter, et al. 2018a. BIODEGRADABLE PLASTIC MULCH AND SUITABILITY FOR SUSTAINABLE AND ORGANIC AGRICULTURE. https://biodegradablemulch.tennessee.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/214/2020/12/Biodegradable-Plastic-Mulch-And-Suitability-for-Sustainable-and-Organic-Agriculture.pdf (accessed 25 September 2025).

Ghimire, S., A.L. Wszelaki, J.C. Moore, D.A. Inglis, and C. Miles. 2018b. The use of biodegradable mulches in pie pumpkin crop production in two diverse climates. HortScience 53(3): 288–294. doi: 10.21273/HORTSCI12630-17.

Griffin-LaHue, D., S. Ghimire, Y. Yu, E.J. Scheenstra, C.A. Miles, et al. 2022. In-field degradation of soil-biodegradable plastic mulch films in a Mediterranean climate. Science of the Total Environment 806. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.150238.

Miles, C. 2017. Oxo-degradable Plastics Risk Environmental Pollution. https://biodegradablemulch.tennessee.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/214/2020/12/oxo-plastics.pdf (accessed 16 September 2025).

Miles, C., L. DeVetter, S. Ghimire, and D.G. Hayes. 2017. Suitability of biodegradable plastic mulches for organic and sustainable agricultural production systems. HortScience 52(1): 10–15. doi: 10.21273/HORTSCI11249-16.

Moore, J.C., and A.L. Wszelaki. 2019a. The use of biodegradable mulches in pepper production in the Southeastern United States. HortScience 54(6): 1031–1038. doi: 10.21273/HORTSCI13942-19.

Moore, J., and A. Wszelaki. 2019b. Paper Mulch for Nutsedge Control in Vegetable Production. (1). https://biodegradablemulch.tennessee.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/214/2020/12/Paper-Mulch-for-Nutsedge-Control-in-Vegetable-Production_FINAL.pdf (accessed 18 September 2025).

Shcherbatyuk, N., S.E. Wortman, D. McFadden, B. Weiss, S. Weyers, et al. 2024. Alternative and Emerging Mulch Technologies for Organic and Sustainable Agriculture in the United States: A Review. HortScience 59(10): 1524–1533. doi: 10.21273/HORTSCI18029-24.

Tiwari, E., and S. Sistla. 2024. Agricultural plastic pollution reduces soil function even under best management practices. PNAS Nexus 3(10). doi: 10.1093/pnasnexus/pgae433.

Tofanelli, M.B.D., and S.E. Wortman. 2020. Benchmarking the agronomic performance of biodegradable mulches against polyethylene mulch film: A meta-analysis. Agronomy 10(10 October). doi: 10.3390/agronomy10101618.