Article and photos by Peg Smith -

As a young child, my experiences with ferns included long walks across Derbyshire moorland where the bracken was twice as tall as I was. Other moorland ferns indicated boggy areas to avoid. Then there was the almost compulsory maidenhair fern house plant that graced the drawing rooms where tea would be taken when visiting relatives or friends. With emigration to Australia, I was introduced to the glorious tree ferns growing fifteen to thirty feet and magnificent staghorn ferns that grew in the upper reaches of eucalypt trees. As much as I would wish to grow ferns in a Yolo County garden, my experiences led me to believe that the grace of a fern would not survive the climate, so they were not included in my plans.

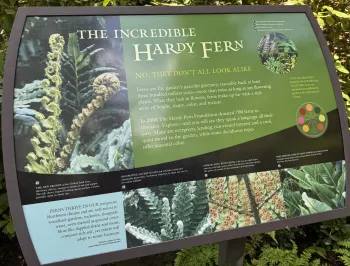

On a visit to Seattle, spending a pleasant afternoon at Bellevue Botanical Gardens, I walked through an area dedicated to ferns. The variations in their sizes, from small to large, and their beautiful features piqued my curiosity. The signage indicated there were 700 types of fern in the garden; surely, there was a variety that would grow in Yolo County.

Ferns are an ancient plant form; the earliest evidence for ferns is in fossils from around 400 million years ago. Most of today’s ferns emerged during the Cretaceous period between 145 and 65 million years ago. Ferns predate flowering plants. They are herbaceous perennials and can be evergreen or deciduous. With no flower or seed production, their reproductive cycle is in two steps. In step one, the fern produces spores on the underside of the fronds. When conditions are right, the spores are released and travel by wind or water and are deposited. A spore then develops into a small heart-shaped gametophyte (sexual life cycle stage of plants). The gametophyte produces both male (sperm) and female (eggs). With moisture, the sperm swim to the egg using flagella, and this fertilization produces a new fern. Most ferns also spread by rhizomes (an underground shoot that produces frond shoots upwards and roots downward). The young shoots that emerge are tightly coiled (fiddleheads) and unfold into mature fronds.

Ferns have great diversity and can be found in mountains, dry, desert rock faces, in water, and in open fields. Places where flowering plants do not thrive will often have ferns that fill that ecological niche. Ferns are primarily used for landscapes, floral arrangements, and house plants. The emerging fronds, fiddle heads, are used as food, as are some roots. Not all ferns can be consumed; some have been found to be carcinogenic.

Ferns, attractive in their own right, can also provide background for floral annual or perennial plantings. If you are looking for ferns to add to your landscape, there are several plants with common names such as foxtail fern that are members of the asparagus family; they are not ferns. UC Master Gardeners of Santa Clara County’s publication Ferns for Your Landscape provides a list of ferns to try in your gardens and discusses the conditions they prefer.