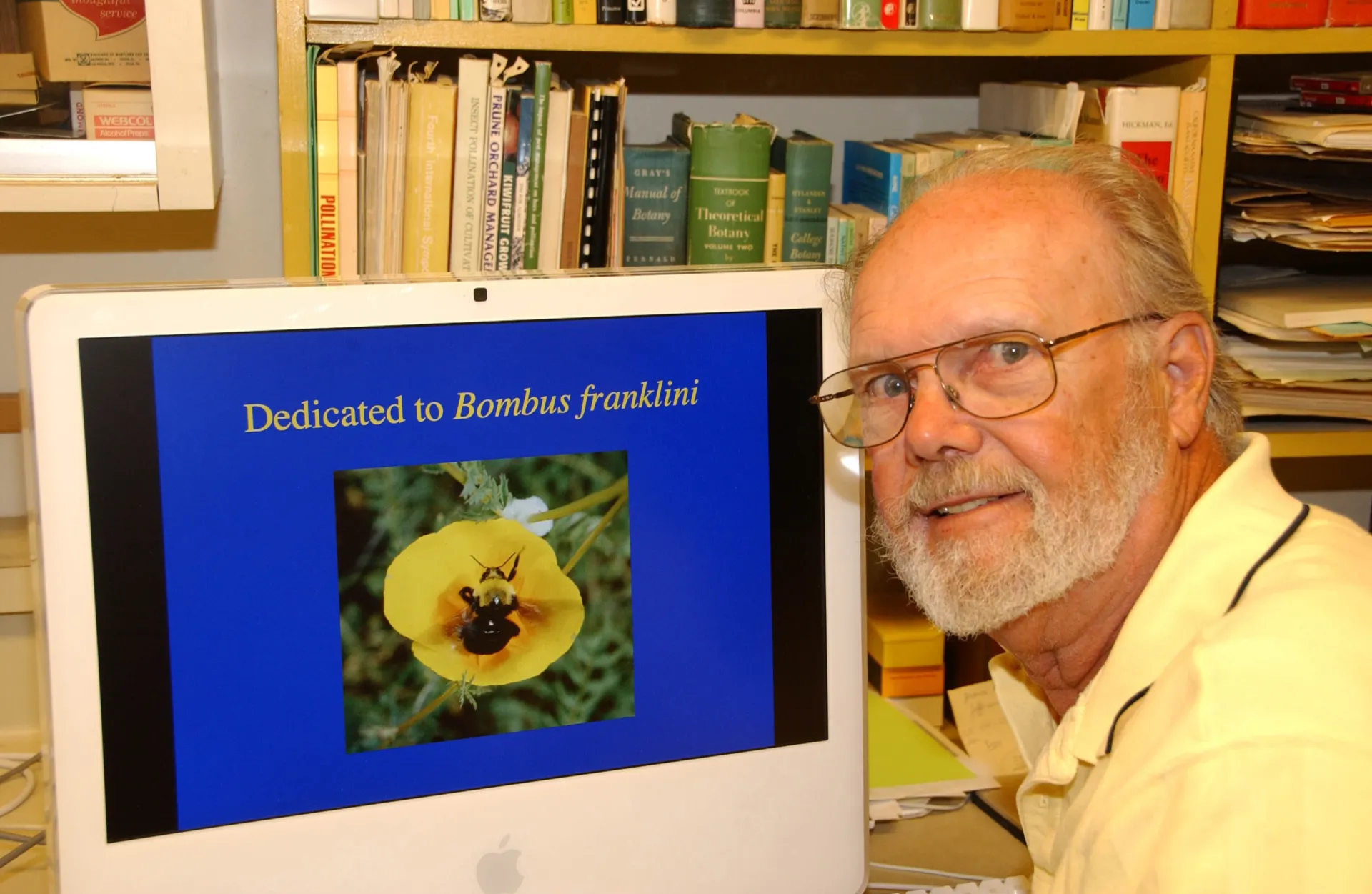

UC Davis Distinguished Emeritus Professor Robbin Thorp, an avid bumble bee conservationist, monitored Franklin's bumble bee, F Bombus franklini, for 21 years, until his death in 2019.

The bee occupies only a narrow range of southern Oregon and northern California. Its range, a 13,300-square-mile area confined to Siskiyou and Trinity counties in California; and Jackson, Douglas and Josephine counties in Oregon, is thought to be the smallest of any other bumble bee in North America and the world.

It is feared extinct.

Thorp desperately wanted it NOT to be.

He sighted 94 of the species in 1998, but only 20 in 1999. The numbers soon began declining drastically (except for 2002):

2000: Nine sightings

2001: One

2002: 20

2003: Three

2004: None

2005: None

2006: One

2007 through 2011: None.

“My experience with the Western bumble bee (B. occidentalis) indicates that populations can remain ‘under the radar’ for long periods of time when their numbers are low,” he told me back in 2011.

He wondered if pathogens factored in the decline of Franklin's bumble bee.

Today a team of scientists, writing about their research in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, said "No."

We posted this today on the UC Davis Entomology and Nematology website. Some excerpts:

"The mysterious population decline of the imperiled Franklin’s bumble bee, which once flourished in a small area of northern California and southern Oregon, is not due to pathogens, but most likely to population bottlenecks and environmental issues, such as fire and drought stressors, according to newly published museum genomic research in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

"A nine-member team, led by conservation geneticist Rena Schweizer of the USDA Agricultural Research Services Pollinating Insects Research Unit, Logan, Utah, collected whole-genome sequence data from museum specimens of Bombus franklini, spanning more than four decades, to reconstruct 300,000 years of the bee’s genetic history.

"Most of the specimens are from the Bohart Museum of Entomology at the University of California, Davis. UC Davis Distinguished Emeritus Professor and bumble bee conservationist Professor Robbin Thorp of the UC Davis Department of Entomology and Nematology monitored the B. franklini population for 21 years, until his death in 2019, and collected specimens. He was instrumental in obtaining species protection under the U.S. Endangered Species Act."

“Understanding what was happening to Franklin's bumble bee was Robbin Thorp's last major project before his death,” said UC Davis Distinguished Professor Emerita Lynn Kimsey, who directed the Bohart Museum for 34 years until her retirement in 2024. She is a co-author of the paper."

PNAS published the paper, “Museum Genomics Suggests Long-Term Population Decline in a Putatively Extinct Bumble Bee,” in its Oct. 20 issue.

Indeed, the project could not have been completed without the work of Thorp and the approval of Kimsey to extract DNA from the specimens. The scientists were able to genomically sample museum specimens at the Bohart for use in their study, with specimens ranging in age from 1950-1998, the only observations after this point. "This allowed us to peek into the genetic history of the species both during the 1950-1998 period,” they said, “and thousands of years prior, using population genomics techniques.”

As the authors pointed out in their significant statement: "The Franklin bumble bee (Bombus franklini), a rare U.S. pollinator, exemplifies the challenges of studying species with small ranges and declining populations that are no longer found in the wild. Using advanced genomic techniques on historical museum specimens, we reconstructed the species’ evolutionary history, revealing critically low genetic diversity and significant population declines since the late Pleistocene. We found that, contrary to previous hypotheses, pathogens likely did not drive initial declines; rather, its extinction vulnerability may have arisen from population bottlenecks and environmental stochasticity over the last 100,000 y. This study underscores the significance of museum collections in unraveling species’ historical population dynamics before modern anthropogenic influences, thereby contributing to understanding extinction risk and helping guide conservation actions."

One of the co-authors is UC Davis doctoral alumnus Michael Branstetter of the USDA-ARS Pollinating Insects Research Unit in Logan, Utah.

See the entire news story here, and more images here.

Resources:

- Robbin Thorp, 1933-2019, UC Davis Department of Entomology and Nematology website, June 7, 2019

- In Memoriam Robbin Thorp, UC Academic Senate

- Remembering the Legendary Robbin Thorp, Bug Squad blog, June 7, 2019

- Robbin Thorp Receives Distinguished Emeritus Professor Award, UC Davis Department of Entomology and Nematology website, Feb. 24, 2015

- 'The Old Man and the Bee' Video, CNN, Nov. 12, 2016

Cover image: Franklin's bumble bee nectaring on lupine near Mt. Ashland in 1999. The bumble bee has not been seen since 2006. (Photo by Robbin Thorp)