The Joy of Grape Jelly (December 2025)

Ariel Patton, UC Master Food Preserver Online Program Volunteer

Hand picked cluster of grapes (Ariel Patton, used with permission).

The thousandth grape drops into the bowl. As the wilting days of summer soften into crisp fall mornings, I pick bunches and bunches of grapes from my garden. I dutifully wash and separate the fruit from the stems, one grape at a time.

I love this annual ritual of making grape jelly. Decades ago, my mom taught kids how to preserve fruits and vegetables through the local 4-H youth group. A half dozen kids would come over and spend summer afternoons chopping loads of peaches and stirring hot, spattering pans of plum preserves. Last year, I became a Master Food Preserver through the University of California Cooperative Extension to teach others how to freeze, can, dehydrate, and ferment California’s finest produce.

Once several pounds of grapes are in a pan, I cook down the fruit. Over the high heat, each grape pops and releases its juice and flavor.

There is a misconception about making jelly: that the best fruits for preserving are overripe or bruised, those weeping berries or gouged pears. This is not true. What is true is that there is a shelf life to everything; some things simply cannot wait. As the fruit gets more mature, there are more sugars, sure. But the pectin and acid, responsible for the lovely, wobbly texture that jelly is named for, declines as the grape turns from puckering green to ripe purple. To preserve produce at its peak demands urgency. Not quite the urgent intensity of a dog’s eyes minutes before dinner, but certainly more than a nagging email.

After the grapes are cooked, liquid resembling mulled wine is left, without the spices or alcohol. Every grape is exhausted of its contents, and it’s now time to strain the mixture to separate the grape skins from the deep purple, flavor-and-pectin-rich liquid that will become the jelly. As the liquid cools overnight in the fridge, tartrate crystals form on the surface. I pass the liquid once more through cheesecloth to remove these tiny snowflakes, the precursor to the mysteriously named Cream of Tartar you find in the baking aisle.

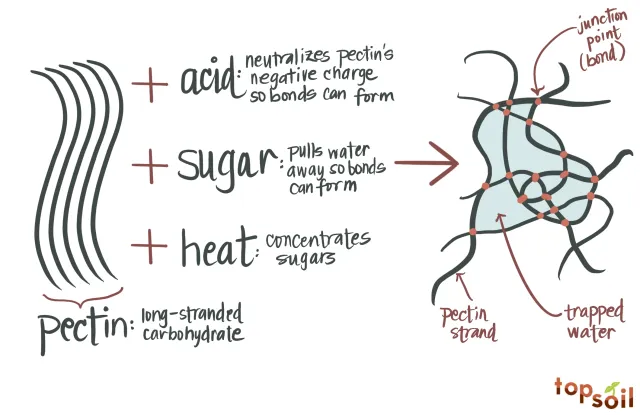

On day two, I carefully pour the strained liquid into a shallow preserving pan along with scoops of warmed sugar and freshly squeezed lemon juice and crank the heat to high. All fruits naturally have some level of pectin. It is a long-stranded carbohydrate; imagine a mane of silky hair. When combined with sugar, acid, and heat, these strands of pectin get tangled up, trapping microscopic pockets of water to create a gel.

Hand-drawn illustration of the chemistry behind pectin gelling (Ariel Patton, used with permission).

I stir and I wait. There are many ways to know if the “gel point” has been reached, the moment the molecules align to form a delectably firm grape jelly. I’ve gotten better at seeing the specific glossiness on the surface, watching as the bubbles ascend more slowly through the boiling liquid, sensing how the spoon traces a deeper pattern in the bottom of the pan. My cheat code is using an instant-read thermometer – once it reads 220°F (exactly eight degrees above boiling at sea-level, my elevation), the cooked jelly is ready.

After many years of using mason jars only as trendy early-aughts decor, I welcomed the gentle rhythm of food preservation during the pandemic. Canning was a way to measure out time, to bottle it up, to tick it off, to mark its passing. In my pantry, the bright jars of apricot preserves, next to chunky peach chutney, followed by smooth pear jam were clear and inarguable evidence that months and seasons were indeed rolling by.

I pour the still-boiling jelly into hot, clean mason jars. I wipe the rim of each jar and tighten the two-piece lids. This also requires attention to get right – tightened enough to seal, but not so tight that it prevents hot air from escaping. One by one, I nestle all the jars into a pot of boiling water to disarm any remaining bacteria. When ten minutes are up, I fish out each jar from the boiling water and place them on the counter to cool.

While there is a thrill in being a one-woman assembly line, making grape jelly is the opposite of how I typically spend my days. It’s inefficient. It’s inconvenient. It’s manual and tedious. As much as I personally enjoy this process, I emphatically do not believe we would have a better food system if everyone had to do this every time they wanted a PB&J. If anything, this annual ritual makes me marvel at the complexity hidden in every bite of food.

Pop! Pop! Pop!

Is there anything more satisfying than hearing the jars on my counter seal, as the tiny breath of hot air within each jar cools and creates a partial vacuum? I’ll save you the two-day journey to find out: the answer is no. Through the alchemy of preservation, what was previously five pounds of grapes threatening to decompose is now six jars of jelly that will last at least a year in my pantry.

To preserve is to grasp the ephemeral and save the very best at its peak for another day. To be able to lick summer off a spoon, past when the leaves have turned and fallen, when our tiny patch of Earth is tilted its very furthest from the sun.